Ashbury 1988

(Reproduced here with kind permission from Leonie Knott)

SAINT DUNSTAN

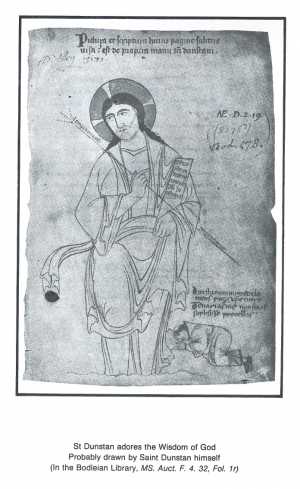

Dunstan’s life extended over the reigns of eight Wessex kings. He was probably born in 909, and would have spent his teenage years at the court of King Aethelstan, the first king to rule over most of what is now England. He would have learnt about the problems of kingship during his most formative years. However, he proved to be rather too puritan for the court’s morals and was sent off to Glastonbury, where he fitted in well with the Benedictine monastic life.

In 943 he was made Abbot by King Edmund, and he immediately instituted reforms, demanding tighter discipline, better morals and greater learning from his monks. In 946 Edmund was succeeded by Eadred, who continued to give Dunstan royal support, but in 955 Eadwig the All Fair became King; he was a playboy who immediately came into conflict with Dunstan and banished him and his strictures to Ghent. Fortunately, Dunstan had to wait only a short time before being brought back by Edgar the Peaceable to be Bishop of Worcester and Bishop of London; in 961 he was made Archbishop of Canterbury and the king’s principal adviser. This was the period of his greatest national influence; his power started to decline after 975, and he then confined himself to his diocesan duties until his death on 19th May 988, 1000 years ago.

DUNSTAN’S KINGS

| Edward the Elder | 899 – 924 |

| Aethelstan | 924 – 939 |

| Edmund | 939 – 946 |

| Eadred | 946 – 955 |

| Eadwig the All Fair | 955 – 959 |

| Edgar the Peaceable | 959 – 975 |

| Edward the Martyr | 975 – 978 |

| Aethelred Evil Council | 978 – 1016 |

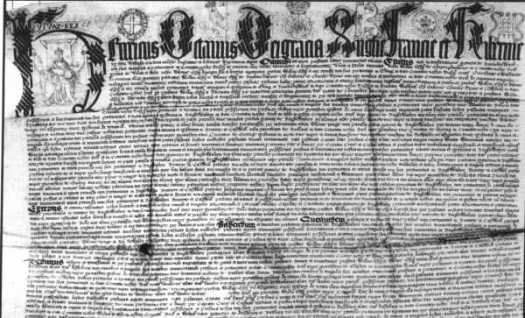

THE ASHBURY CHARTER

There is a Saxon Charter of 947 in which King Eadred gave a certain Edrig 20 measures of land in Ashdown; the boundaries of the land are carefully described but, apart from the Ridgeway, none can now be precisely indentified. Ashdown is the old name for the Berkshire Downs, with the Ridgeway running along the northern edge.

The Charter had a very important footnote added to it at a later date. It says that Edrig “…manerium, quod nunc vocatur Aysshebury… dedit Sancto Dunstano tunc abbati Glaston…”: Edrig “…gave the manor, which is now called Ashbury… to Saint Dunstan then Abbot of Glastonbury.” We do not know when the footnote was written but, if it is the original version and not a modified copy, it must have been after Dunstan’s death in 988 or he could not have been referred to as “Saint” Dunstan. We may speculate that King Eadred wanted to reward Dunstan in some way, and asked him what he would like; if oral tradition is correct, Dunstan wanted a site to build a hostelry for journeys between Glastonbury, Winchester, Canterbury and London. So Eadred persuaded Edrig to give up Ashbury, which became Glastonbury’s only Berkshire possession. This link, forged in about 950, lasted for nearly 600 years until the dissolution of the monasteries. Ashbury’s entry in the Domesday Book says that “Glastonbury Abbey holds Ashbury and always held it.” “Always” is a slight exaggeration to describe a period of 135 years, but at least King William’s commissioners were satisfied about Glastonbury’s title; probably the Charter footnote was part of the evidence.

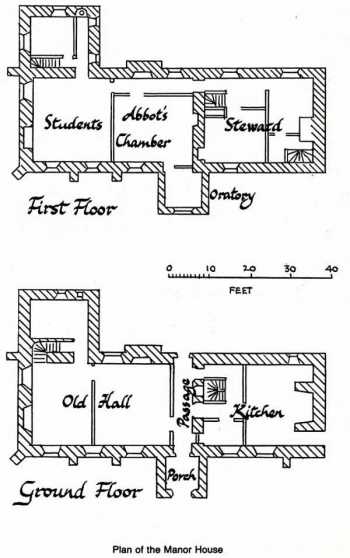

THE MANOR HOUSE

Glastonbury let out a large part of the manor land to tenants — three were important enough to be named in the Domesday Book — and the abbot will have appointed a steward to farm his own “demesne” or home farm land and to look after his other interests. The site of the present manor house was used for earlier demesne farms, probably back to the 10th century. It is not unreasonable to suppose that Dunstan gave the instructions for founding Ashbury’s first Saxon church and the first manor house, both of which have long since given way to more modern buildings.

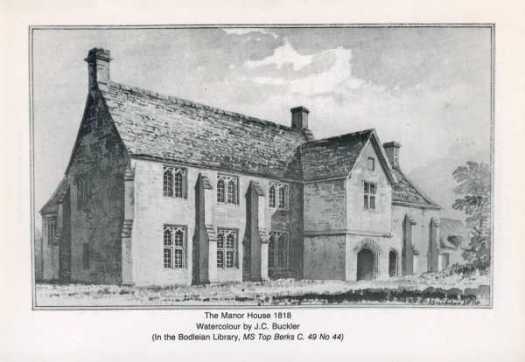

The present manor house was built in 1488, 500 years ago, during John Selwood’s abbacy, and the style suggests that he sent his Somerset craftsmen up to Ashbury to build it. The walls are constructed mainly of the local chalk, but a harder stone has been brought in where greater strength is required: for windows, buttresses, and for some lower parts of the west and south walls. The design had to satisfy two requirements, as a house for the abbot’s steward and as a hostelry for all grades of visitor, from the abbot himself down to Glastonbury students studying at Oxford.

The ground floor is divided into two by a passage running north and south from the entrance porch; the east half was the service end and the west was the main hall.

Upstairs, the steward’s rooms were above the service end, students lived in the west end, and there was a central section for the abbot and other important visitors. A small oratory is above the entrance porch, leading off the central chamber, presumably for the abbot’s use.

The house was researched and described in detail in 1966, and it was then believed to be one of the best, if not the best preserved manor house in Berkshire. This was attributed to the fact that, until Mr Spence bought it in 1956, it had been occupied only by tenant farmers for over 300 years: neither absentee owners nor tenants would willingly spend money on expansion, alteration or renovation. Walls, carved bosses, fireplaces, panels, windows, arches with quatrefoils, staircases, roof beams — these and many more features can still be seen just as they were when built 500 years ago.

ASHBURY’S LORDS

| Dunstan | 943 – 957 | Robert | 1224 – 1235 |

| Egelward | c 962 | Michael de Amesbury | 1235 – 1252 |

| Elfstan | Roger Forde | 1252 – 1261 | |

| Sigebar | 965 – 973 | Robert de Petherton | 1261 – 1274 |

| Beorthored | c 1000 | John de Taunton | 1274 – 1290 |

| Brithwin | 1017 – 1027 | John de Cancia | 1290 – 1303 |

| Egelward | 1027 – 1053 | Geoffrey Fromond | 1303 – 1323 |

| Elgelnoth | 1053 – 1078 | Adam de Sodbury | 1323 – 1335 |

| Thurstan | 1078 – 1100 | John de Breinton | 1335 – 1342 |

| Herlewin | 1101 – 1120 | Walter de Monington | 1342 – 1375 |

| Sigfrid | 1120 – 1126 | John Chynnock | 1375 – 1420 |

| Henry of Blois | 1126 – 1171 | Nicholas de Frome | 1420 – 1456 |

| Robert | 1171 – 1178 | Walter More | 1456 |

| Henry de Soliaco | 1179 – 1192 | John Selwood | 1456 – 1493 |

| Savaric | 1192 – 1205 | Richard Beere | 1493 – 1524 |

| Jocelin | 1205 – 1219 | Richard Whiting (martyred) | 1524 – 1539 |

| William Vigor | 1219 – 1223 |

Dissolution 1539

King Henry VIII

| Sir William Essex & descendants | 1544—1620 |

| Jacob Hardrett | 1620—1625 |

| William Craven & descendants | 1625—1956 |

Part of the Title Deed granting the Manor to Sir William Essex in 1544

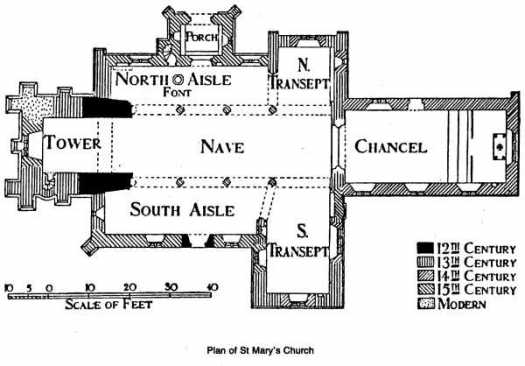

ST MARY’S CHURCH

The church sits above the village, south towards the Ridgeway. It is said that some of the stones built into the wall surrounding the churchyard came from a stone circle, like a small version of Avebury Circle. It is most unlikely that the church was actually built on the site of a stone circle — more level ground would normally have been chosen for the latter — but one small fact hints that the story might be true: a 16th century document mentions a field called Wheleacre, and fields of that name are frequently the sites of stone circles. This field may have been on the level ground north of the village, and the circle may have been the earliest religious “building” in the parish. There was certainly a Saxon church, because it is mentioned in the Glaston-bury Abbey Chronicle for the 10th century and in the Domesday Book; it will have been wooden, almost certainly on the site of the present church which was started in the 12th century.

Remains of the first stone Norman church are still visible at the west end of the north and south nave walls and in the arch over the south doorway — although, the latter was originally the west doorway arch. The aisles, transepts and tower were added in the 13th century, and the chancel in the 14th.

It used to be thought that churches were enlarged mainly to meet the needs of a growing congregation, but it now seems more likely that it was the accepted way to glorify and pacify an all-powerful God: an insurance for the after-life.

Glastonbury, like other abbeys, became increasingly rich up to the early part of the 14th century, and Ashbury benefited from that wealth. Then two things happened: the Black Death in 1348-49 caused a major depression, and the churches built over the previous 200 years started to need large sums spent on them for repair and maintenance. The need for maintenance has never ceased. The churchwardens’ accounts show that in the period 1791 – 94 nearly £190 was “disbursed on seating and repairing” — not far short of £10,000 today. Seventy years later the equivalent of £4000 was paid out on repairs, and in 1964 an appeal was launched to help offset a £5000 repair bill — over £30,000 at today’s prices. Nowadays it costs more than £300 simply to have an expert carry out a 5 yearly inspection to find out what repairs are needed.