(Reproduced here with kind permission from Ann Disbury)

The area known today as the parish of Ashbury has been continuously lived in for almost 5000 years. The Saxons in the 9th century called it Aescaesbyries, the “Camp of the Ash Trees”. This new guide book covers those parts of the village, hamlets and countryside where evidence can still be seen today of that long human occupation. The guide is published to coincide with the Ashbury Festival of 1983.

David Disbury

We are grateful to Mr. David Disbury for producing this guide to the village. All proceeds from the sale of this booklet will go to St. Mary’s Ashbury, Restoration Fund.

Derek Burden

On entering the parish from the south, by way of the B4000 road from Lambourn, the traveller is passing over the remains of a Romano-British field system. The fields cover several thousand acres where coins, pottery and other Roman artefacts have been found. To the south of Upper Wood, part of Ashdown Park, can be seen a large bank and ditch which once encircled the whole of Upper Wood. Constructed in 1240 at the instruction of Abbot Michael of Glastonbury, this Park-Pale was designed to protect the Abbot’s woodland against wandering animals and to serve as a boundary. Just below the embankment is a large, now dry, dew pond. Stand in the hollow of the pond and the hollow trackways that led down from the hills to this animal watering place can still be seen. A few yards up the bank and to the west of the road, just inside the bank, and between it and the wood, once stood a Roman farm. This was one of three within the parish, the others are to the west of Botley Copse and on Odstone Down to the north-east.

As the road continues towards Ashdown House sarsen stones can be seen on the left. Legend had it that they are sheep turned to stone by Merlin, the magician to King Arthur. In fact they are a sand stone left here by the retreat of the great ice flows of thousands of years ago. Over the years thy have been taken for use in ancient tombs, old cottages and barns and to build walls around the woods of Ashdown.

Behind the stones and visible through a break in the trees can be seen Ashdown House. This pretty Dutch-style hunting box was build at the instigation of William, 1st Earl of Craven. Craven had the house built for the exiled Elizabeth of Bohemia, sister to Charles the First and known to history as ‘The Winter Queen’. Unfortunately she died at Craven’s London home and never saw the beautiful house and park that

is now part of the National Trust and open to the public on certain days each month. Inside can be seen a magnificent collection of Stuart paintings depicting the Queen’s children and other famous personalities from the Civil War period of English history.

Behind the house, past the remains of the avenue of trees which once lined the road out to the connecting road between Lambourn and the Vale below, is Alfred’s Castle. This is a small Iron Age hill-fort used during that period as a home for Celtic farmers and protection for their animals. Looking south from the banks of the camp towards the downs can be seen three humps on the sky-line. These are the Idstone Three Barrows, all that remains of a Bronze-Age cemetery. Other barrows from this time have been ploughed out all over the downs above the village.

Continuing along the road you leave Ashdown Park with Hailey Wood on the left. This part of Ashbury was once called Rough Thorn Farm. It was known to local people as Red Barn from the Elizabethan brick cottages that once stood here. It has been claimed that the cottages were built to house the keepers of the beacons, part of a chain of warning fires from all over England at the time the country was threatened with invasion by the Spanish Armada.

The road now passes over what has been called ‘The Oldest Road in the World’, The Ridgeway. The Icknield Way, an ancient track, begins at the Wash and ends south of Salisbury Plain. The Ridgeway is the winter path of this track which passes through Berkshire.

Alongside the Ridgeway can be found numerous pre-historic sites. By following the track a few hundred yards to the east from the main road you will find probably the most famous, the now restored Wayland’s Smith chambered long barrow. Local legend has it that ‘at this place formerly lived an invisible smith and, if a traveller’s horse had lost a shoe, he had no more to do than bring the horse to this place with a piece of money, and by leaving both might come again and find the money gone, but the horse new-shod’. In fact the ‘Smithy’ is a New Stone Age long barrow or burial place. It is unique in this country in that the mound covers an even earlier burial mound which contained one complete skeleton and a pile of loose human bones. Later Neolithic farmers changed their style of burial rites and constructed the great mound chambered megalithic tomb we see today.

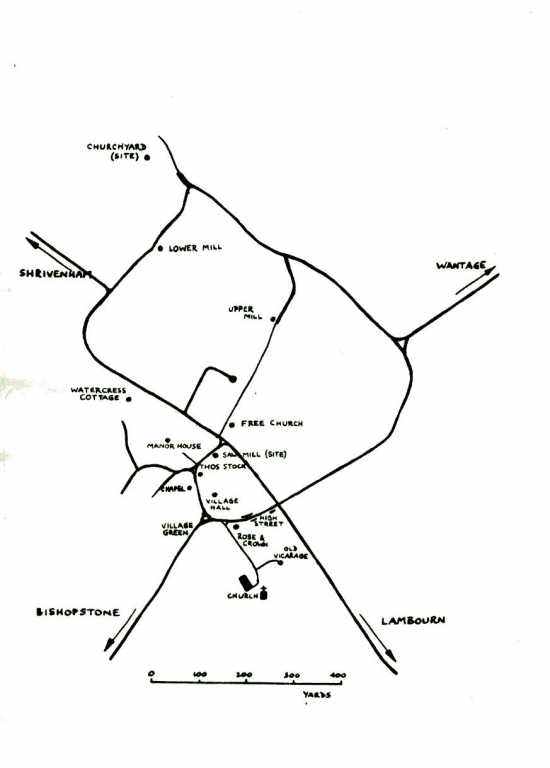

At the foot of Ashbury Hill is the cross roads with the B4507; by turning left you enter Ashbury High Street. The corner shop is the latest in a long line that have served the village for the past 150 years. Traditionally the shop has always gone with the Post Office, at least from the 1860’s. Postmasters then had to deliver the letters or arrange for this to be done. One such postman died in the great blizzard of 1881 after leaving Ashdown House on his round. Almost opposite the shop can be seen a brick built cottage which was once part of a blacksmiths. During the 19th century Ashbury boasted a number of craftsmen, needed to meet the demands of a rural parish. There were wheel-wrights, carpenters, masons, builders, cordwainers (or shoemakers) and the women often worked as dressmakers. At one time Idstone was famous for its bonnet makers. At the turn of the century one Uriah Partridge was the hurdle maker and the story of his early life, his tools and craft appear in Alfred Williams’ ‘Villages of the White Horse’.

The Rose and Crown public house has also found its way into English literature. Thomas Hughes in his ‘Scouring of the White Horse’ recounts the story of the Longcot may-pole being stolen by Ashbury lads and taken to the Rose and Crown where it was out through the window of the bar. A riot started when people from Longcot attempted to get it back. Other villages heard of the fracas and soon there were fights in and around the inn. The vicar of Uffington finally ordered the may-pole to be cut up as logs for the poor, thus sealing the fate of the last may-pole in the Vale of the White Horse. Public houses once brewed their own beer and Carter’s Ashbury Ale became well known in the area. Originally the inn was thatched but this was accidentally burnt during the Second World War and with it a cottage opposite in Church Lane.

The Rose and Crown public house has also found its way into English literature. Thomas Hughes in his ‘Scouring of the White Horse’ recounts the story of the Longcot may-pole being stolen by Ashbury lads and taken to the Rose and Crown where it was out through the window of the bar. A riot started when people from Longcot attempted to get it back. Other villages heard of the fracas and soon there were fights in and around the inn. The vicar of Uffington finally ordered the may-pole to be cut up as logs for the poor, thus sealing the fate of the last may-pole in the Vale of the White Horse. Public houses once brewed their own beer and Carter’s Ashbury Ale became well known in the area. Originally the inn was thatched but this was accidentally burnt during the Second World War and with it a cottage opposite in Church Lane.

The lane by the inn leads up to St. Mary’s Church. The first reference to a church in Ashbury appears in the Domesday Book. The building, probably of wood, stood on or near the present church site. What we see today has evolved from the 12th century. Traces of the earliest fabric can be seen in the walls of the  nave at the western end, below the tower and best of all on the outside of the south door. Experts suggest that the first stone building consisted of an aisless nave, one and a half times the length of the present tower, with north and south doorways. The 13th century additions consisted of aisles, transepts and a new tower which incorporated part of the old nave walling. Early in the following century the chancel was rebuilt and the north porch added. The west window, the embattled parapet of the tower and the nave roof are all 15th century. The latter was reconstructed around 1600 but the plaster ceiling is a much later addition. In 1872 the church was reseated ‘upon condition that all seats be free…..suitable provision being made for the use of the poor inhabitants’. The church has numerous memorials to past villagers. The brass to John Walden dated 1350 was known as Berkshire’s oldest brass. The pulpit is a memorial to the Rev. W Matthews who died preaching here in January 1870. The Thomas Stock tablet over looks the gravestone of the Royalist William Phillips of Odstone. Under the tower are lead tablets with the initials of past church-wardens. The kneelers and seat cushions were made by ladies, and a few gentlemen, of the parish in memory of Richard Geoffrey Lawrence who died in September, 1972. The tower clock was placed in memory of Richard Hull Lawrence. The Lawrence family farmed Rectory Farm, Idstone for well over 100 years. The north transept was originally a chantry and in November, 1926, it was dedicated to the memory of Evelyn, Countess of Craven, the windows coming from her private chapel at Ashdown Park.

nave at the western end, below the tower and best of all on the outside of the south door. Experts suggest that the first stone building consisted of an aisless nave, one and a half times the length of the present tower, with north and south doorways. The 13th century additions consisted of aisles, transepts and a new tower which incorporated part of the old nave walling. Early in the following century the chancel was rebuilt and the north porch added. The west window, the embattled parapet of the tower and the nave roof are all 15th century. The latter was reconstructed around 1600 but the plaster ceiling is a much later addition. In 1872 the church was reseated ‘upon condition that all seats be free…..suitable provision being made for the use of the poor inhabitants’. The church has numerous memorials to past villagers. The brass to John Walden dated 1350 was known as Berkshire’s oldest brass. The pulpit is a memorial to the Rev. W Matthews who died preaching here in January 1870. The Thomas Stock tablet over looks the gravestone of the Royalist William Phillips of Odstone. Under the tower are lead tablets with the initials of past church-wardens. The kneelers and seat cushions were made by ladies, and a few gentlemen, of the parish in memory of Richard Geoffrey Lawrence who died in September, 1972. The tower clock was placed in memory of Richard Hull Lawrence. The Lawrence family farmed Rectory Farm, Idstone for well over 100 years. The north transept was originally a chantry and in November, 1926, it was dedicated to the memory of Evelyn, Countess of Craven, the windows coming from her private chapel at Ashdown Park.

As you leave the churchyard there is a watching cottage, constructed during the age of the body-snatchers. A few yards north of the church is the old vicarage which was partially destroyed during the Civil War by a gunpowder explosion. Opposite the church gate is a building that once served as a village hall. Once three condemned cottages, the villagers, with financial help from Lady Craven, had them converted into the Jubilee Hall. It served for many years for social functions, as a base for the Home Guard and even the travelling cinema that toured the Vale. The heavy stones that line the churchyard wall are claimed by some to be a ‘mystic circle’ similar to Avebury but there is little evidence to support such a claim.

At the foot of Church Lane stands ‘Billy’s Cottage’. For many years it was the house of Billy Johnson, one of the last of the Ashbury shepherds. Billy was also a bell-ringer and he would leave the downs to ring at St. Mary’s and then return to his flock. He recalled for me the old custom of burying a shepherd with a piece of wool so that they would know in Heaven why he had missed so many church services on earth. His hut on the hill was lit by a candle or oil lamp and so was his cottage, for he refused such ‘moderns’ during his lifetime.

The Village Green is small and here stands the War Memorial. To the right is the National School building where many of those named on the memorial were taught short years before they died in Flanders, France, Greece and in other ‘foreign fields’.

The Village Green is small and here stands the War Memorial. To the right is the National School building where many of those named on the memorial were taught short years before they died in Flanders, France, Greece and in other ‘foreign fields’.

In 1724 money was raised by local gentlemen and Lord Craven for a Charity School, ‘Whereby children of the poor could be rescued from a miserable life of vagrancy and theft…’. The children were to be ‘real objects of charity between the ages of 7 and 12’. The National School was built in 1864 and consisted of one large hall, heated by stoves, with a dais at the centre where the master stood to supervise. Attendance at first was at the discretion of the parents or employers but in 1880 attendance was made compulsory and in 1891 education became free. Ink froze in the wells and paper and pens had to be scrounged locally. Often it proved easier to close the school than enforce attendance during the bad weather or epidemics. When beaters were required on the estate the school closed as truancy was rife. During World War 1 over 1200 attendances were lost as children replaced men in the fields. Violence was not uncommon. Darlington, headmaster in the early 1900’s, had his leg kicked by a boy kept in after school. He had a pen thrown into his face and on another occasion he was punched off his bicycle on the Idstone Road for caning his assailant’s younger brother. The present school, which stands behind the National School, was opened in two stages in 1959 and 1961.

One of the cottages north of the school and opposite the Methodist Chapel housed England’s first Sunday School. Thomas Stock, Curate at Ashbury between 1775 and 1778, began a Sunday School in the chancel of the church. As the numbers grew Lord Craven put a cottage at his disposal, probably the same building that housed the Charity School. Stock left Ashbury for Gloucester where he met Robert Raikes, who is usually credited with founding the Sunday School movement, but it is almost certain he took the idea from Thomas Stock.

The Methodist Chapel dates from 1926. Methodism was popular with agricultural labourers and the first licence for a meeting was granted at Reading Sessions for meetings to be held in the home of Richard Webb in 1832.

The road in front of the Manor House turns towards King’s Close, once King’s Homestead, a farm house. It runs to Berrycroft Farm, another 18th century building. On the left is a tractor shed and at the back can be seen the doorway to what was once Pound’s bakehouse. Here local women would bring their own bread to be baked and their meat on Sundays for roasting.

After the church the most impressive structure in Ashbury is Chapel Manor Farm. It probably takes its name from the licence granted to it in the 14th century for a private chapel to be used in the Manor for the tenant farmer. The demesne, or home farm, covered just over 600 acres and was owned until 1539 by  Glastonbury Abbey. Experts date the present building to 1488 when the Wars of the Roses finally came to an end. Richard Mayew, vicar of Ashbury, was chaplain to both Richard III and Henry VII who defeated Richard at Bosworth Field. Manor courts were held at Ashbury every three weeks. About 1261 there was a croft, two acres of garden, an orchard and a fishpond. In 1274 a kitchen, dovecote and outbuildings were added. By 1290 a further room was added inside the main building. Ashbury was Glastonbury’s only Manor in Berkshire. They used the house to lodge students on their way to and from Oxford. Later the Manor was divided into two parts, one court for the Abbot and the other for the tenant farmer. When the Craven family bought the Manor they continued to let it to tenant farmers and it would appear the rent was seldom paid. In 1956 the house and farm were purchased by Mr. Robert Spence who had been a tenant from 1927. The house we see today is built of chalk and stone and is roofed in Cotswold slate. The upper part of the porch was rebuilt in brick in 1697 and the initials ‘T.W.’ for Thomas White, the tenant farmer, appear above the doorway. Today it is very much a modern working farm but with the church-like windows and buttresses it is not difficult to visualise the reeve, brewer, hayward, woodward and shepherd paying their customs to the Steward at Ashbury Manor Court.

Glastonbury Abbey. Experts date the present building to 1488 when the Wars of the Roses finally came to an end. Richard Mayew, vicar of Ashbury, was chaplain to both Richard III and Henry VII who defeated Richard at Bosworth Field. Manor courts were held at Ashbury every three weeks. About 1261 there was a croft, two acres of garden, an orchard and a fishpond. In 1274 a kitchen, dovecote and outbuildings were added. By 1290 a further room was added inside the main building. Ashbury was Glastonbury’s only Manor in Berkshire. They used the house to lodge students on their way to and from Oxford. Later the Manor was divided into two parts, one court for the Abbot and the other for the tenant farmer. When the Craven family bought the Manor they continued to let it to tenant farmers and it would appear the rent was seldom paid. In 1956 the house and farm were purchased by Mr. Robert Spence who had been a tenant from 1927. The house we see today is built of chalk and stone and is roofed in Cotswold slate. The upper part of the porch was rebuilt in brick in 1697 and the initials ‘T.W.’ for Thomas White, the tenant farmer, appear above the doorway. Today it is very much a modern working farm but with the church-like windows and buttresses it is not difficult to visualise the reeve, brewer, hayward, woodward and shepherd paying their customs to the Steward at Ashbury Manor Court.

To the east of the Manor House lies a deep hollow, often called a moat. Here springs rise that once supplied a cress-bed and Ashbury’s Barkside Watergrist Mill. The mill, like the church, is mentioned in Domesday Book. Its boundaries were alongside Berrycroft field, down to Pulpit bridge, up by Pulpit field and Pound Piece and round to where the modern bungalows stand. There were garden grounds with stables, trees, woods, mill ponds, mill gates, flood gates and a sheep washing pool. At washing time extra help had to be brought in and thousands of sheep would be dipped, shorn and the wool packed and carted to Marlborough. Early in the 19th century the mill fell into disuse and all the work went to North Mill and the Kingstone mills.

On the site of the bungalows* the Craven Estate had a saw-yard. Trees were selected and felled in Ashdown Woods and Botley Copse and were brought to the saw pit for cutting into usable wood for gates, sheds and repairs undertaken by the estate carpenters.

The B4000 road with the Manor on the left and Pound Piece on the right descends into the hamlet of Kingstone Winslow. Although part of the parish it has always been a separate holding in early records. The Lower Mill has been partially restored with a reconstructed wheel. Kingstone once had a small Baptist Chapel, erected in 1865, it was pulled down in 1935. All that remains is a small graveyard within a clump of trees where a few local Baptists were buried. Turning right and up the lane towards the downs leads to Kingstone Farm. The farmhouse is chalk fronted and two storeys high and dates from about 1730. During the 19th century the farm covered almost 500 acres and employed over 30 labourers and farm servants. For many years the tenant was Heber Hufrey who carved oak brackets on the pulpit in the church.

Below the farmhouse is Kingstone Upper Mill with its great mill pond fed by a number of springs. Alfred Williams visited the mill in 1913 when it was in use. He left not only a description of the practical working of the mill but a word picture of its beauty and scenic position, ‘each slope with graceful elms, of exquisite shape, which tower to great heights’.

This guide has taken the visitor from Ashdown to Kingstone Winslow. By travelling a short distance from the village, but remaining within the parish, a number of interesting historic sites can be seen.

- Trip the Daisy is the name of a house in Idstone. Once a beerhouse called the Greyhound its unusual name comes from that of a famous coursing hound.

- Odstone Farm. Believed to be the site of a deserted Medieval village.

- Chapelwick. Also known as Vicarage Close, a small chapel was built here in the 13th century by Andrew de la Wyke.

- North Mill. The mill was abandoned early in the 19th century, all that remains are the mill dams and the site of the gardens and cottages.

- Zulu Buildings on the road to Shrivenham take their name from the time when a number of generals from the Zulu Wars stayed at Rectory Farm, Idstone.

* See map (saw yard)